Perpendicular Bisector Theorem

Perpendicular Bisector Theorem (Proof, Converse, & Examples)

Perpendicular

All good learning begins with vocabulary, so we will focus on the two important words of the theorem. Perpendicular means two line segments, rays, lines or any combination of those that meet at right angles. A line is perpendicular if it intersects another line and creates right angles.

Bisector

A bisector is an object (a line, a ray, or line segment) that cuts another object (an angle, a line segment) into two equal parts. A bisector cannot bisect a line, because by definition a line is infinite.

Perpendicular bisector

Putting the two meanings together, we get the concept of a perpendicular bisector, a line, ray or line segment that bisects an angle or line segment at a right angle.

Before you get all bothered about it being a perpendicular bisector of an angle, consider: what is the measure of a straight angle? 180°180°; that means a line dividing that angle into two equal parts and forming two right angles is a perpendicular bisector of the angle.

Perpendicular bisector theorem

Okay, we laid the groundwork. So putting everything together, what does the Perpendicular Bisector Theorem say?

How does it work?

Suppose you have a big, square plot of land, 1,000 meters on a side. You built a humdinger of a radio tower, 300 meters high, right smack in the middle of your land. You plan to broadcast rock music day and night.

Anyway, that location for your radio tower means you have 500 meters of land to the left, and 500 meters of land to the right. Your radio tower is a perpendicular bisector of the length of your land.

You need to reinforce the tower with wires to keep it from tipping over in high winds. Those are called guy wires. How long should a guy wire from the top down to the land be, on each side?

Because you constructed a perpendicular bisector, you do not need to measure on each side. One measurement, which you can calculate using geometry, is enough. Use the Pythagorean Theorem for right triangles:

Your tower is 300 meters. You can go out 500 meters to anchor the wire's end. The tower meets your land at 90°. So:

You need guy wires a whopping 583.095 meters long to run from the top of the tower to the edge of your land. You repeat the operation at the 200 meter height, and the 100 meter height.

For every height you choose, you will cut guy wires of identical lengths for the left and right side of your radio tower, because the tower is the perpendicular bisector of your land.

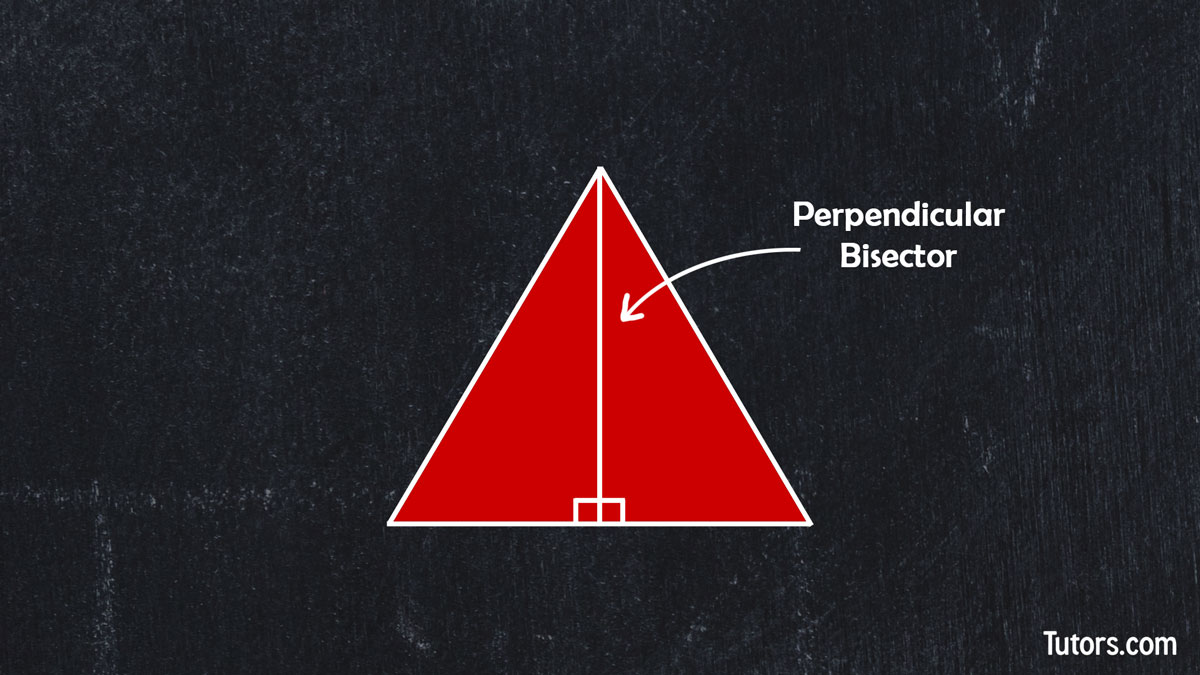

Proving the perpendicular bisector theorem

Behold the awesome power of the two words, "perpendicular bisector," because with only a line segment, HM, and its perpendicular bisector, WA, we can prove this theorem.

We are given line segment HM and we have bisected it (divided it exactly in two) by a line WA. That line bisected HM at 90° because it is a given. This means, if we run a line segment from Point W to Point H, we can create right triangle WHA, and another line segment WM creates right triangle WAM.

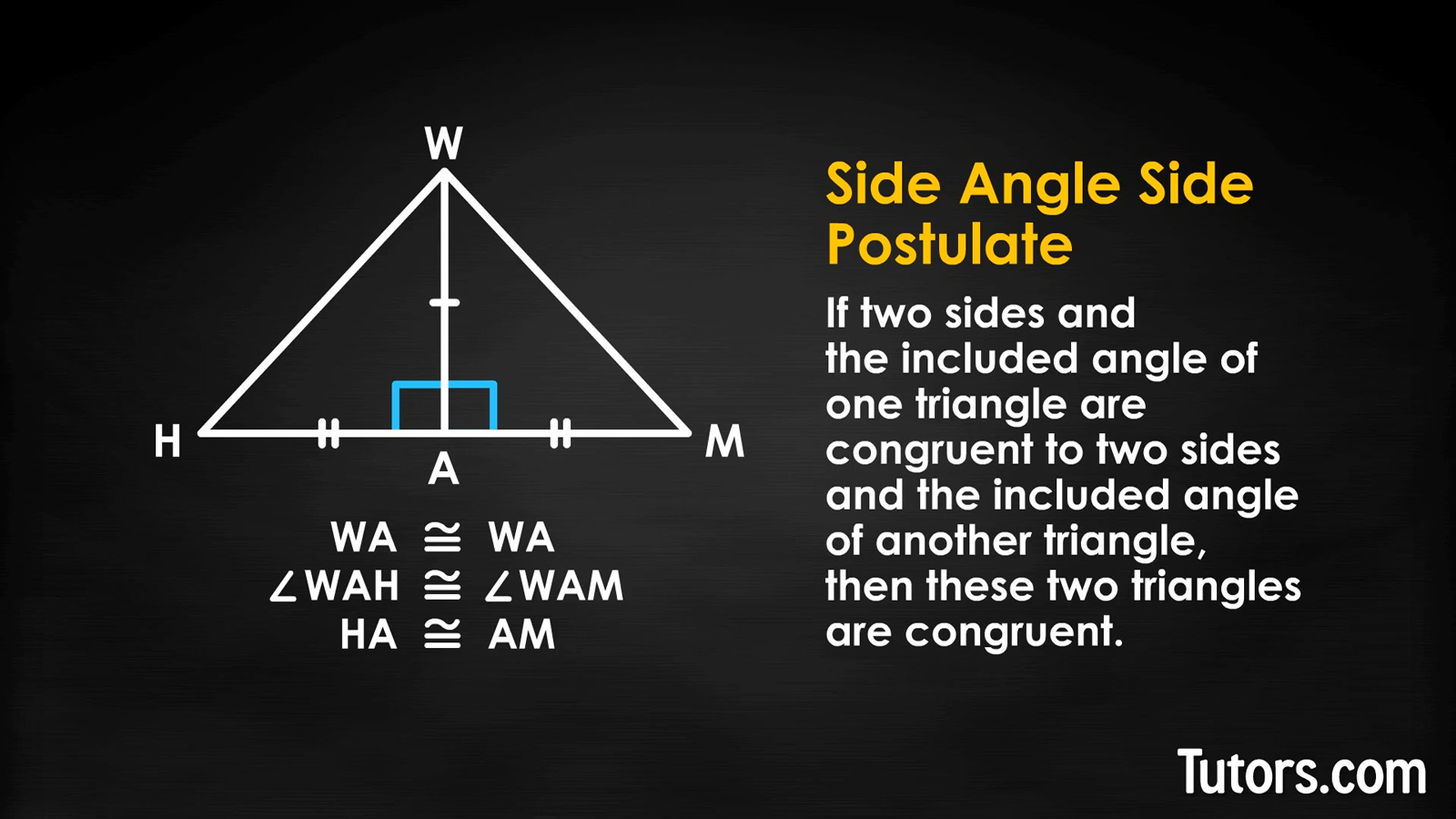

What do we have now? We have two right triangles, WHA and WAM, sharing side WA, with all these congruences:

WA ≅ WA (by the reflexive property)

∠WAH ≅ ∠WAM (90° angles; given)

HA ≅ AM (bisector; given)

What does that look like? We hope you said Side Angle Side, because that is exactly what it is.

That means sides WH and WM are congruent, because CPCTC (corresponding parts of congruent triangles are congruent). WHAM! Proven!

Practice proof

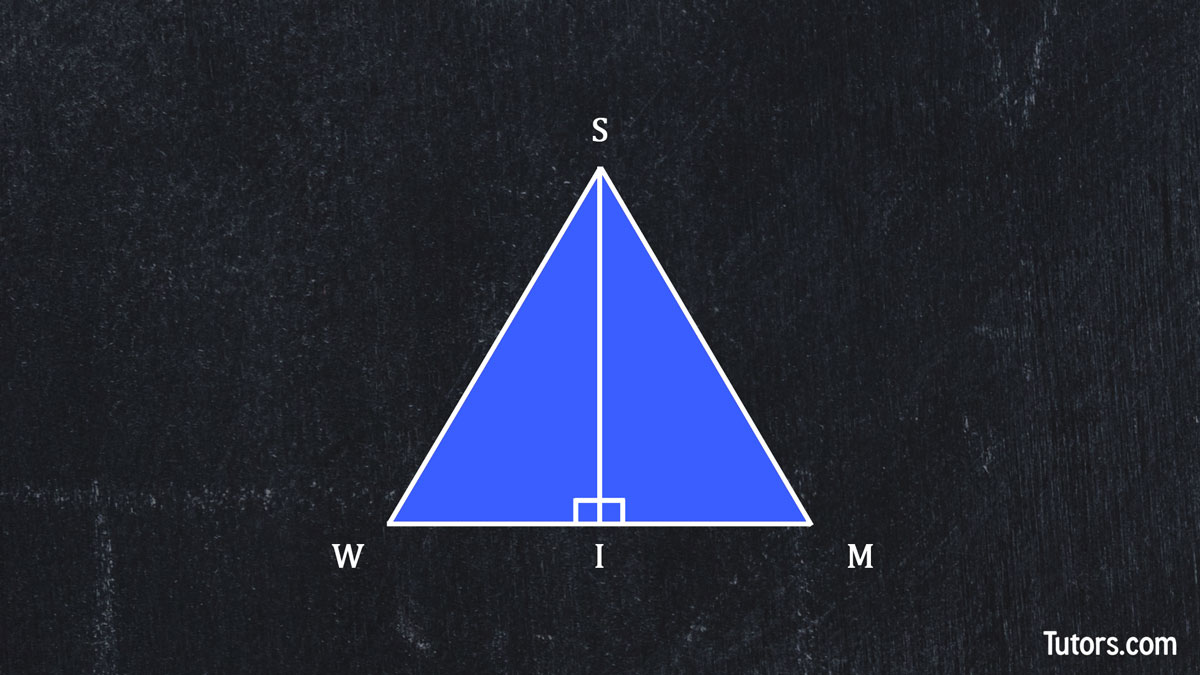

You can tackle the theorem yourself now. You will either sink or swim on this one. Here is a line segment, WM. We construct a perpendicular bisector, SI.

How can you prove that SW ≅ SM? Do you know what to do?

Construct line segments SW and SM.

You now have what? Two right triangles, SWI and SIM. They have right angles, ∠SIW and ∠SIM.

Identify WI and IM as congruent, because they are the two parts of line segment WM that were bisected by SI.

Identify SI as congruent to itself (by the reflexive property).

What does that give you? Two congruent sides and an included angle, which is what postulate? The SAS Postulate, of course! Therefore, line segment SW ≅ SM.

So, did you sink or SWIM?

Converse of the perpendicular bisector theorem

Notice that the theorem is constructed as an "if, then" statement. That immediately suggests you can write the converse of it, by switching the parts:

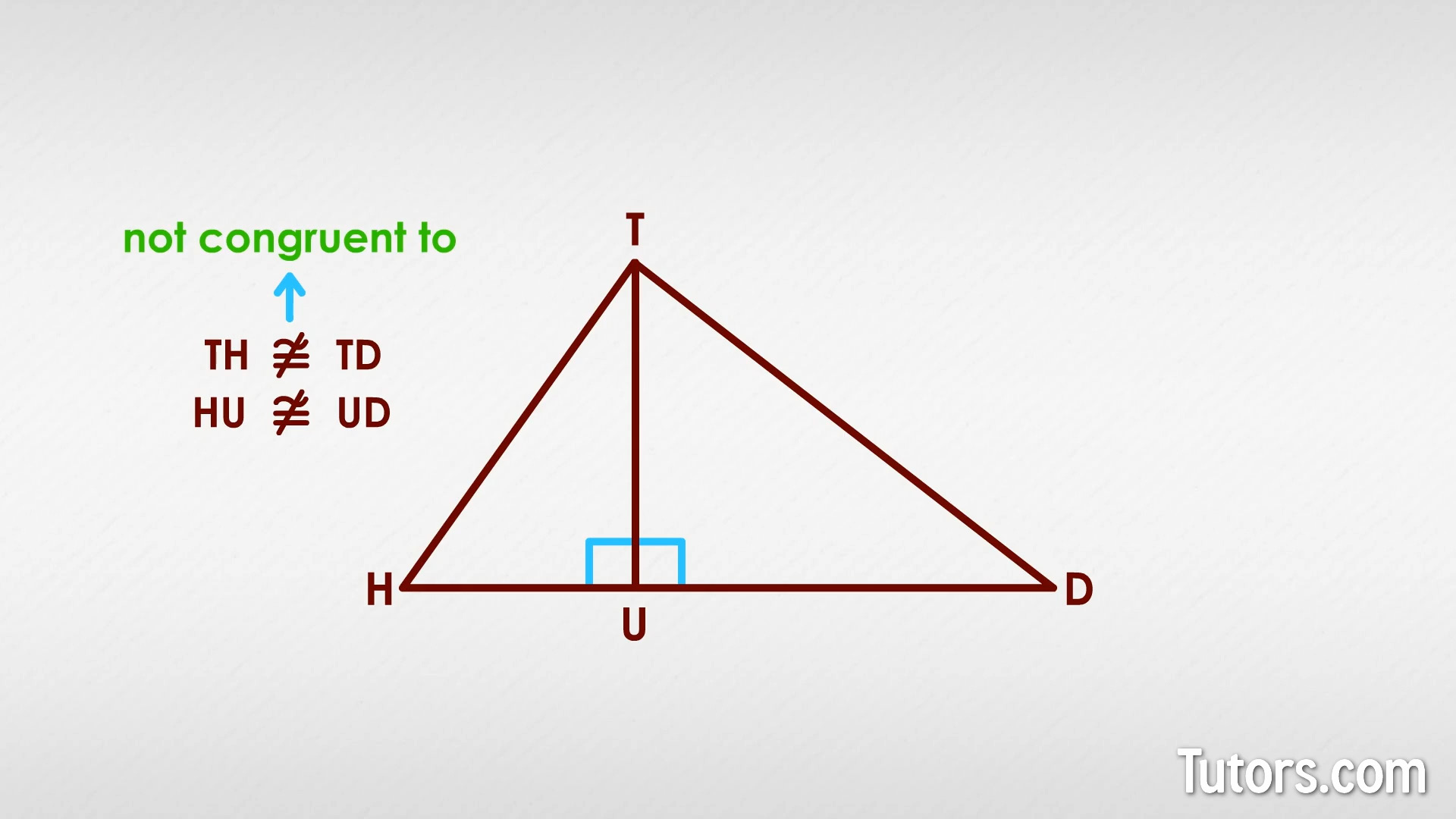

We can show this, too. Construct a line segment HD. Place a random point above it (but still somewhere between Points H and D) and call it Point T.

If Point T is the same distance from Points H and D, this converse statement says it must lie on the perpendicular bisector of HD.

You can prove or disprove this by dropping a perpendicular line from Point T through line segment HD. Where your perpendicular line crosses HD, call it Point U.

If Point T is the same distance from Points H and D, then HU ≅ UD. If Point T is not the same distance from Points H and D, then HU ≆ UD.

You can go through the steps of creating two right triangles, △THU and △TUD and proving angles and sides congruent (or not congruent), the same as with the original theorem.

You would identify the right angles, the congruent sides along the original line segment HD, and the reflexive congruent side TU. When you got to a pair of corresponding sides that were not congruent, then you would know Point T was not on the perpendicular bisector.

Only points lying on the perpendicular bisector will be equidistant from the endpoints of the line segment. Everything else lands with a THUD.

Lesson summary

After you worked your way through all the angles, proofs and multimedia, you are now able to recall the Perpendicular Bisector Theorem and test the converse of the Theorem. You also got a refresher in what "perpendicular," "bisector," and "converse" mean.