Independent Clause — Definition & Examples

Independent clause definition

An independent clause is defined as a group of words that contains a subject and verb and expresses a complete thought. An independent clause can stand alone as a complete sentence, even if it is part of a larger sentence.

What makes an independent clause?

An independent clause or independent sentence is formed when you have a subject doing some action. The subject in a sentence is the noun performing some action. The verb in a sentence is the action the subject performs. An independent clause can appear in simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences.

How to identify independent clauses

To check whether a phrase is an independent clause, ask yourself two questions:

Who is doing something in the sentence?

What are they doing?

If you can answer both questions, you have an independent clause.

Independent clause examples

The simplest sentence is an independent clause. You can create a one-word imperative sentence with an understood subject (you) that is an independent clause:

Run!

Who is doing something? You, the reader or listener, is doing something. What are you doing? You are commanded to run. You are the subject, and run is the verb.

If the phrase contains a subject and verb and expresses a complete thought, it is also an independent clause:

Billy-Bob ran!

Billy-Bob ran from the ferocious groundhogs!

Billy-Bob ran from the ferocious, mutant groundhogs!

Independent vs. dependent clause

You can contrast the independent clause with a dependent clause, a phrase that cannot stand on its own:

Upon seeing the horde of groundhogs, Billy-Bob ran!

If we try to write just the dependent clause as a sentence, it makes no sense:

Upon seeing the horde of groundhogs.

Since you have no idea who did something, you do not have an independent clause.

Types of sentences using independent clauses

Independent clauses are used to create several types of sentence structure, and it can be difficult to identify independent clauses, especially in compound, complex, or compound-complex sentences.

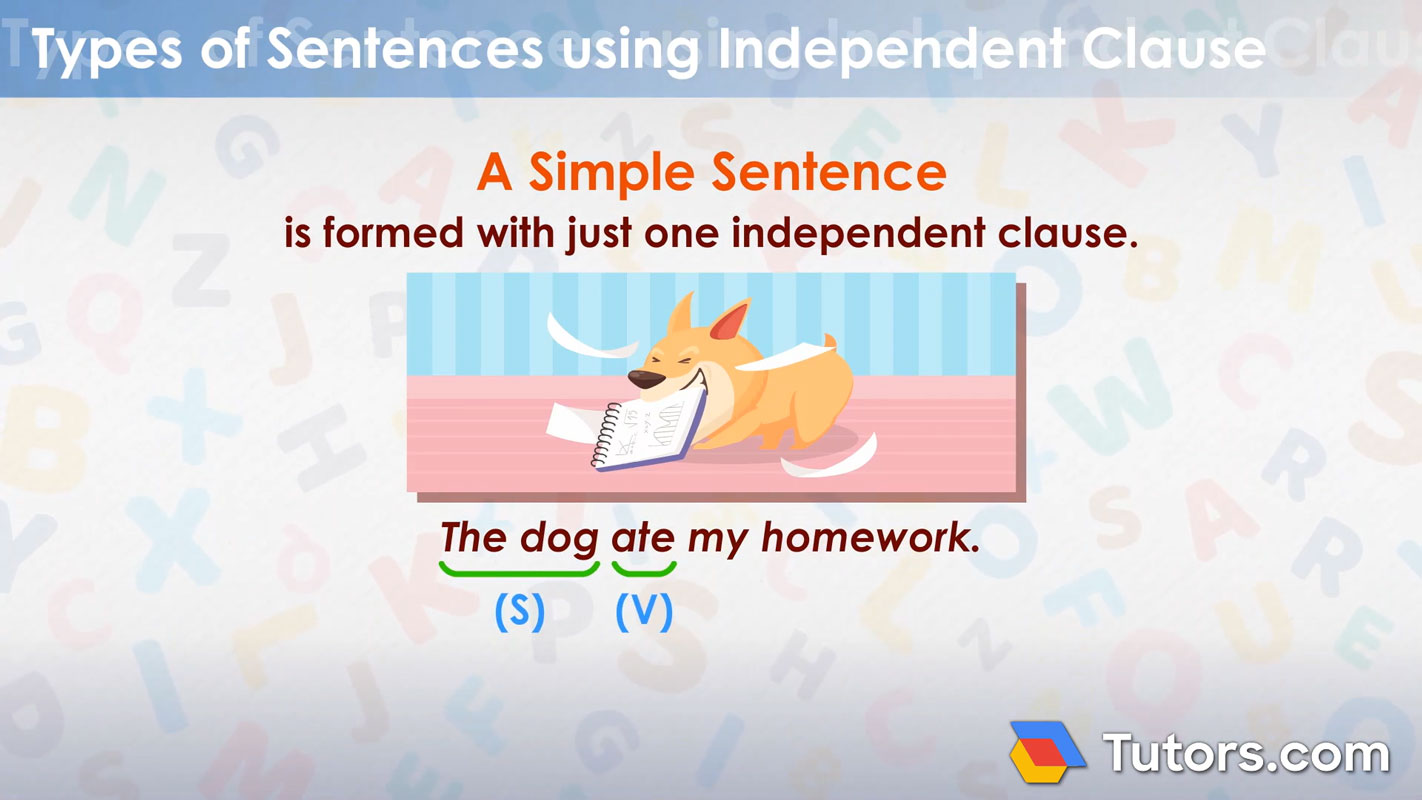

Simple sentences

A simple sentence is formed with just one independent clause. An example is:

The dog ate my homework.

The dog is the subject, and eating is the verb.

When you join several clauses together is when it gets difficult to find the independent clauses.

Compound sentences

Compound sentences join two or more independent clauses with either a semicolon or coordinating conjunction, easily remembered with the acronym FANBOYS:

For

And

Nor

But

Or

Yet

So

Below are two compound sentences from Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Treasure Island.”

This one uses a semicolon to join the first independent clause to the second independent clause:

All day he hung round the cove or upon the cliffs with a brass telescope; all evening he sat in a corner of the parlour next the fire and drank rum and water very strong.

This one uses a comma and a coordinating conjunction (connecting word):

At first we thought it was the want of company of his own kind that made him ask this question, but at last we began to see he was desirous to avoid them.

In both examples, the two sentences can be broken into two separate sentences and still grammatically correct.

Complex sentences

Complex sentences contain independent and dependent clauses. The dependent clause is attached to the independent clause with a subordinating conjunction.

Several common subordinating conjunctions are:

although

because

before

even though

if

since

until

when

“Treasure Island” has plenty of examples. Here are three examples:

For just then, although the sun had still an hour or two to run, all the echoes of the island awoke and bellowed to the thunder of a cannon.

Certainly, since the mutiny began, not a man of them could ever have been sober.

I'm to be a poor, crawling beggar, sponging for rum, when I might be rolling in a coach!

In the third example, the first part before ", when" can be its own sentences. This means it is the independent clause. The part after the ", when" is a subordinate clause as it cannot stand alone as a complete sentence.

Compound-Complex sentences

Compound-complex sentences wrap together at least two independent clauses and at least one dependent clause. Complex sentences tend to be long and use both coordinating and subordinating conjunctions in their construction.

Here is a fine example from Stevenson’s classic:

I could not help joining, and we laughed together, peal after peal, until the tavern rang again.

Run-on sentences

Eliminating the proper punctuation or appropriate conjunction will cause sentences with independent clauses to become run-on sentences. Any dependent clauses become fragments.

Neither run-on sentences nor fragments are good for your writing, though they can appear in fiction since they mimic everyday oral language. They are rarely appropriate for formal, academic, or nonfiction writing.

Run-on sentences often include the weak comma splice, which is when a lowly comma is asked to do the work of a semicolon:

Perfectly fine: Pirates plunder. Mothers worry.

Run-on sentence: Pirates plunder mothers worry.

Comma splice: Pirates plunder, mothers worry.

Remedy: Pirates plunder, and mothers worry.

Repair run-on sentences by inserting a period between independent clauses, replacing a comma with a semicolon, or linking them with a comma and coordinating conjunction.

Fragments

Fragments are dependent clauses incorrectly carrying the weight of independent clauses. Everyday conversation is rich with fragments. We speak for brevity and clarity, not for posterity.

When writing formally, avoid fragments. When capturing dialogue, use fragments.

Perfectly fine: While the pirates plundered the ship, the child’s mother worried for the lad’s safety.

Fragment: While the pirates plundered the ship. The child’s mother worried for the lad’s safety.

Repair sentence fragments by adding either a subject or verb, whichever is missing. You can also connect the fragment, as a dependent clause, to its independent clause.